“What is it that I see?”

For the holiday season, listen to the In the Groove, Jazz and Beyond show: Autumn and Thanksgiving.

You may also enjoy going through the archives of the In the Groove, Jazz and Beyond podcast:

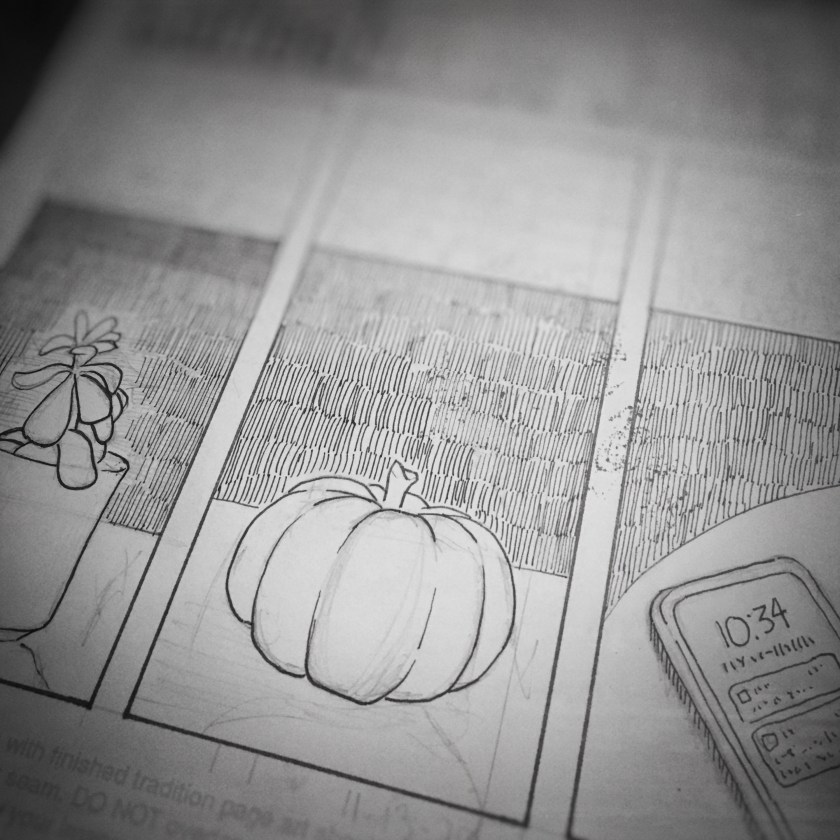

The pressure to perform and succeed at holidays stresses everyone. The lists of things to do, people to see, and places to go is overwhelming. That is the simple and delightful plot of the 1970s film A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving. A favorite scene is when the Peanuts characters prepare the Thanksgiving feast: buttered toast, popcorn, pretzels, jelly beans, and an ice cream parfait.

One year, our family put together a Charlie Brown Thanksgiving feast of toast, popcorn, pretzel sticks and gummy bears (could not find jelly beans at the convenience store) to share. The snacks were placed in brown paper lunch bags and shared at gatherings. The disappointment was that most of those who received the Charlie Brown Thanksgiving snack bags had never scene the film. Or did not remember the feast items. But I am grateful for the lesson.

Are you thankful for a challenge or disappointment that turned out to be better than expected? What teaching or teacher are you grateful for this year? Name a person in your life currently who is a blessing. Who is a person in your past for whom you are grateful? What is something you learned to do that is a blessing?

There so many things and people to be thankful for that an individual might be able to fill a bare November maple tree with bright red paper thanksgiving leaves.

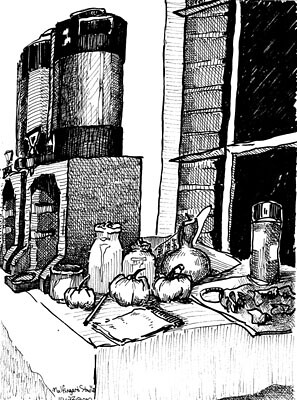

Every small town barbershop is a source of stories. Sad stories. Funny stories. Good stories. Confessions. Tips on how to buy an automobile. Tips on where to find an honest mechanic. The country barbershop was a community center. A public square.

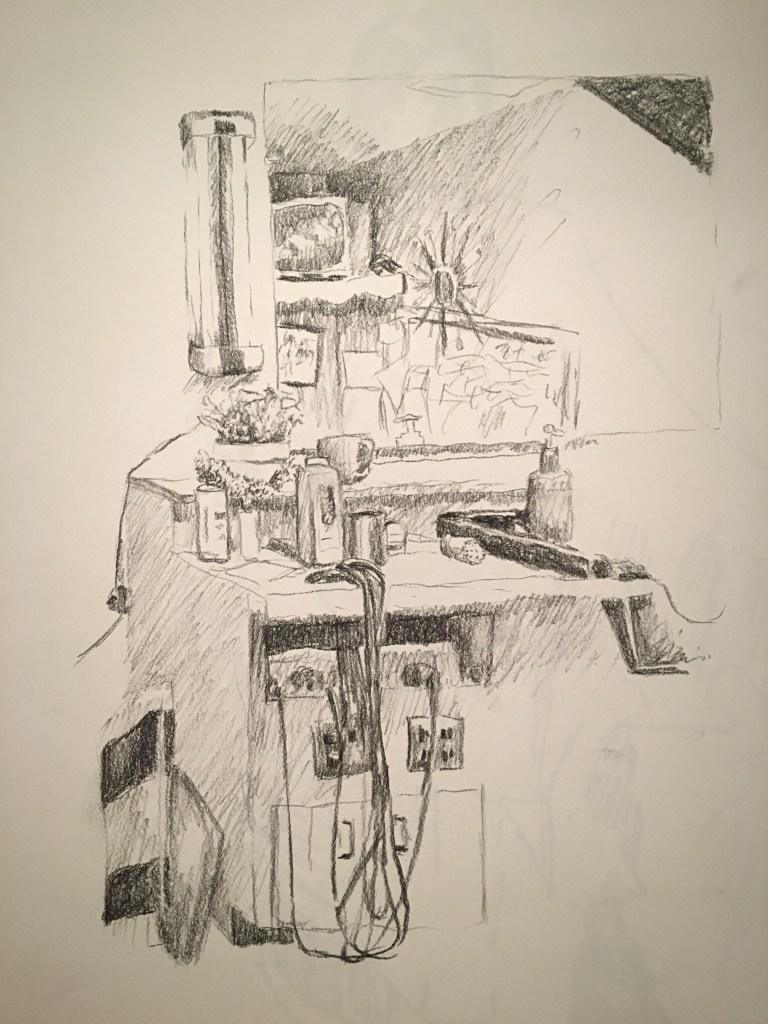

This charcoal sketch captures the old barbershop on Main Street back in the 1990s. No television. No music system playing in the background. Just a couple decks of playing cards. A cribbage board. Back issues of Field & Stream magazine. And a lot of stories.

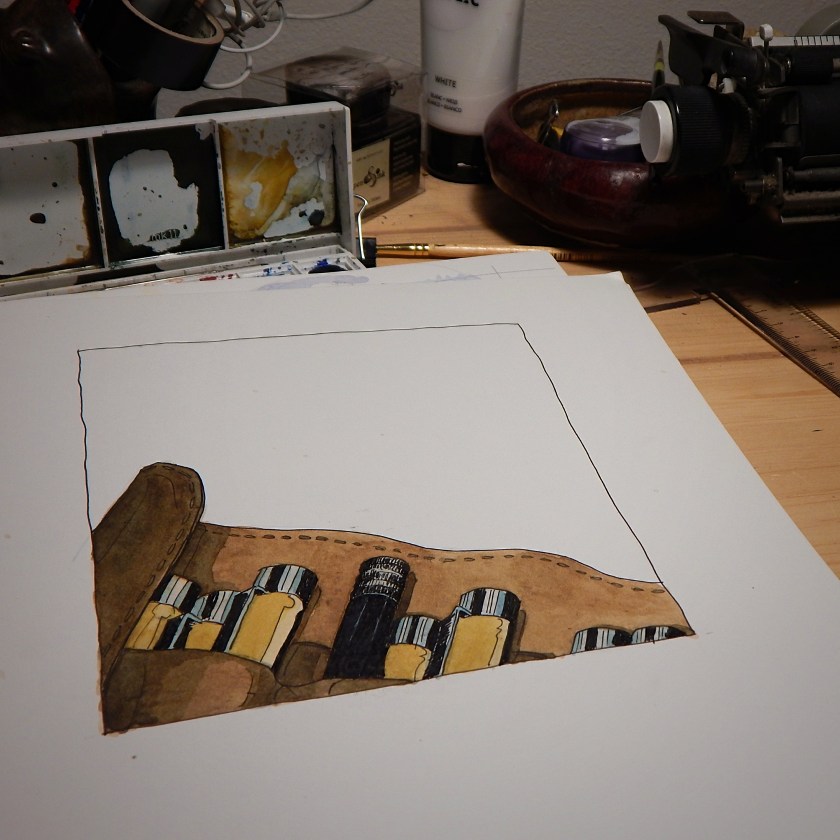

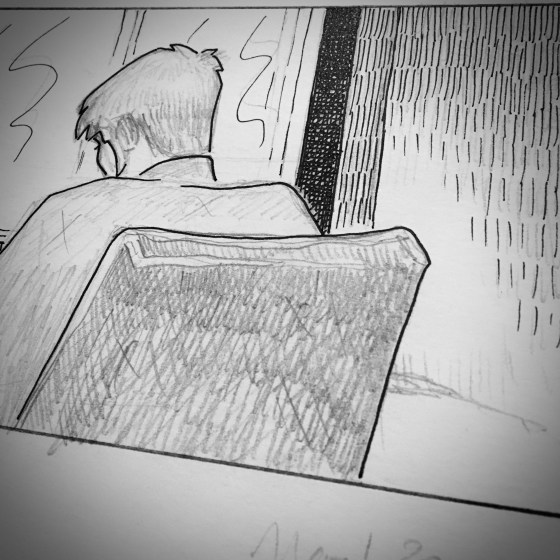

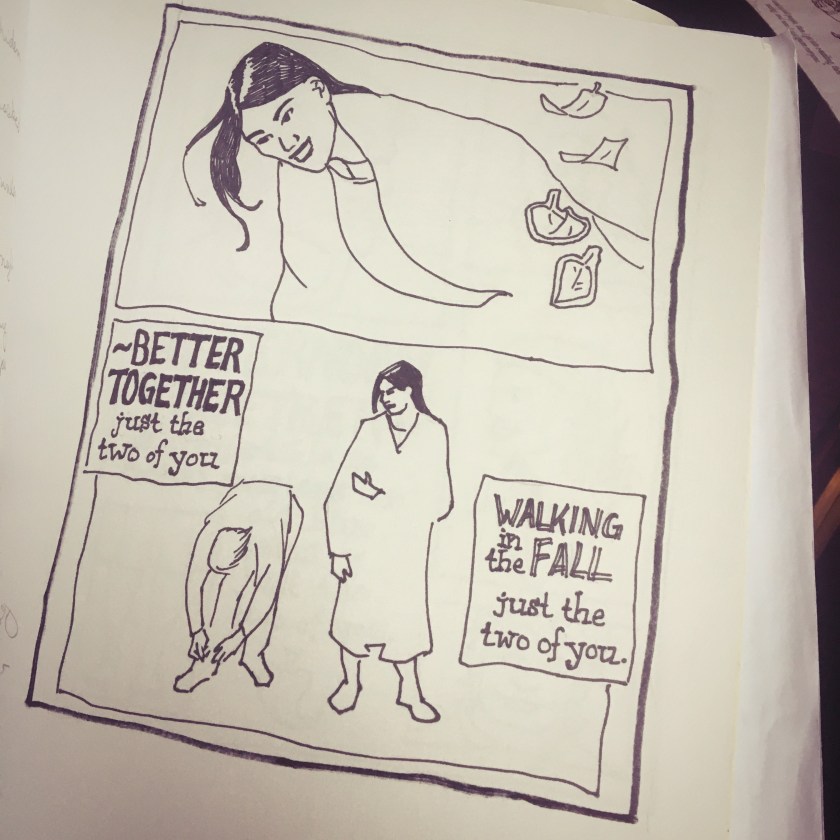

Most nights I look at this series of drawings and try to remember where I left off. Do I have time to finish a one-page drawing? Or one part of a drawing on a page?

The project began years ago. The script is incomplete. The character model sheet shifted. A fellow graphic designer called the original drawings “cartoony”. So, I shifted the drawings to something more realistic and representational. But the grammar of it seems confusing.

He sketches. He draws.

He sketches a page a night. He draws cartoony pictures.

Intransitive verbs. Transitive verbs. Is there such thing as transitive art? Intransitive art? Does the artwork transfer action to someone of something? Does artwork use a direct object? Is the artwork a direct object and the action the artist?

He drew. Last night, he drew.

Last night, he drew a cartoon picture. Last night, he drew a cartoon picture for a story he wrote, but did not finish.

This is confusing. English grammar. Transitive verbs. Intransitive verbs.

Tonight, he changed.

Tonight, he changed creative direction. Tonight, he drew a representational picture for a story he wrote .

What is grammar? Grammar is the skill of expanding core principles of any topic. Grammar provides the base for dialectic. Dialectic furnishes the foundation for rhetoric.

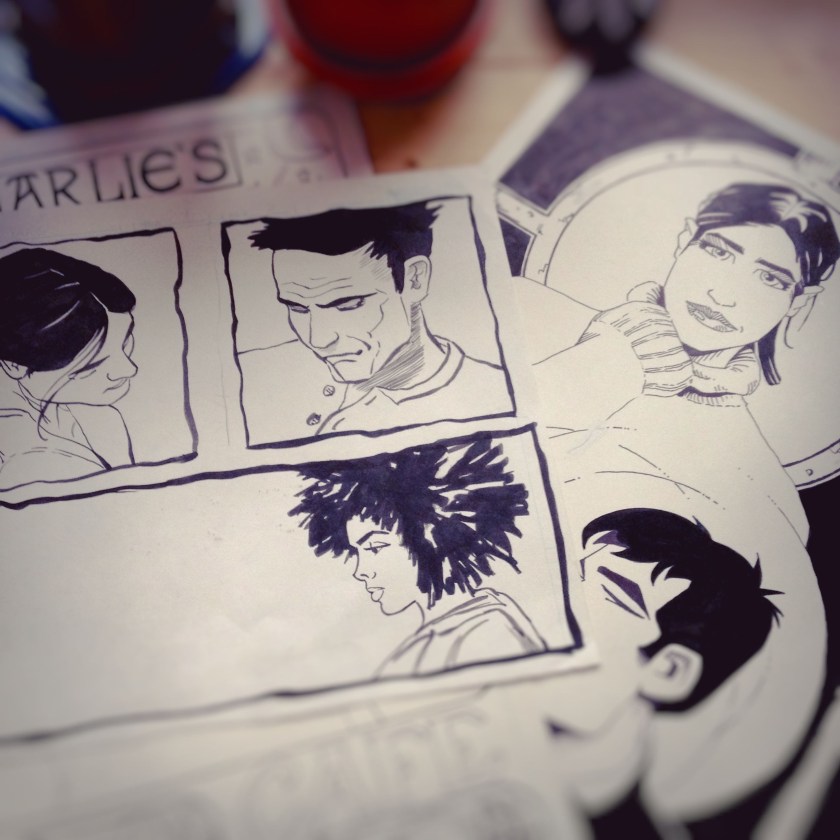

Pen transfers ink to paper. Ink forms points and lines. Points and lines for compositions…

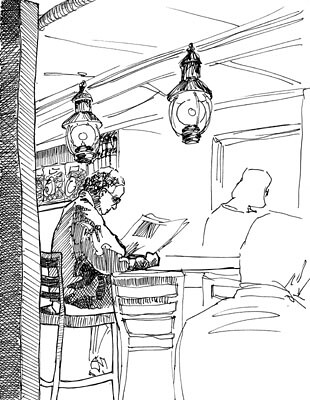

As a drawing exercise, I reclaim old illustration paper that has been damaged in some form or fashion. Maybe it was ink or paint that bleed from a top page to the paper underneath. Maybe it is page that I erased pencil lines so many times the paper fibers feather the ink when it is applied. Whatever the case, a couple drawings and the use of my Sakura Pigma Micron pens provide an art exercise.

The challenge of creating analog art in a digital world is the only people to see and experience it are those who receive it–who physically hold the Bristol paper with ink illustrations in their hands. It is a great temptation to showcase the art on social media for the ephemeral likes of affirmation and validation. But the experience of sharing art in-person is intimate and memorable.

Is this sentimental? Or wistful desire toward a time and place where people were present and engaged? The value of creating something tangible and shared among family and friends avoids parasocial relationships. The glare of digital praise is alluring, but lonely.

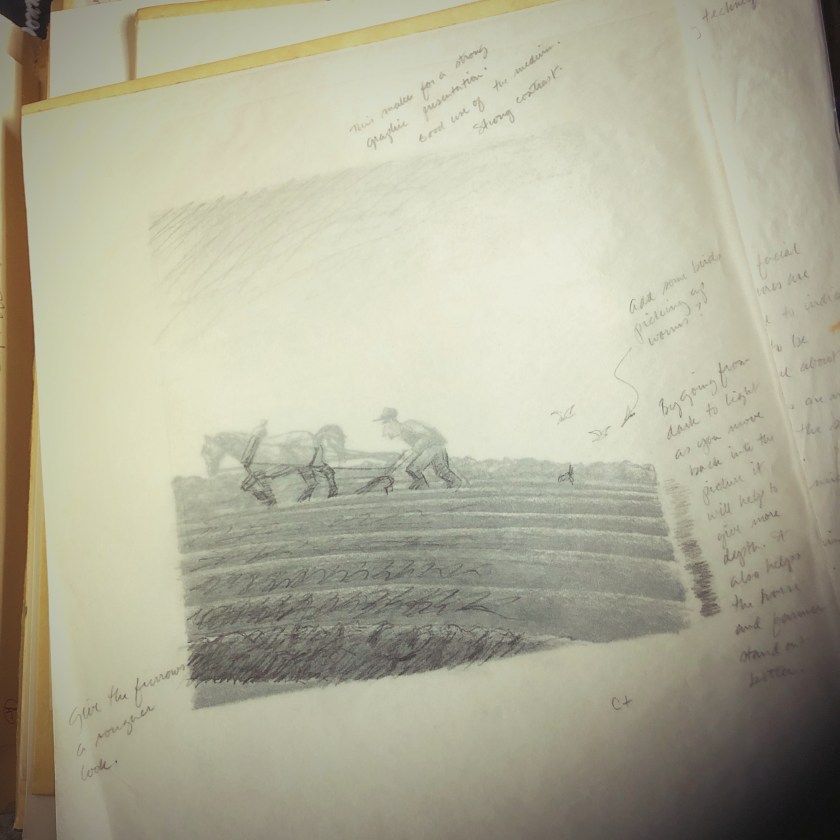

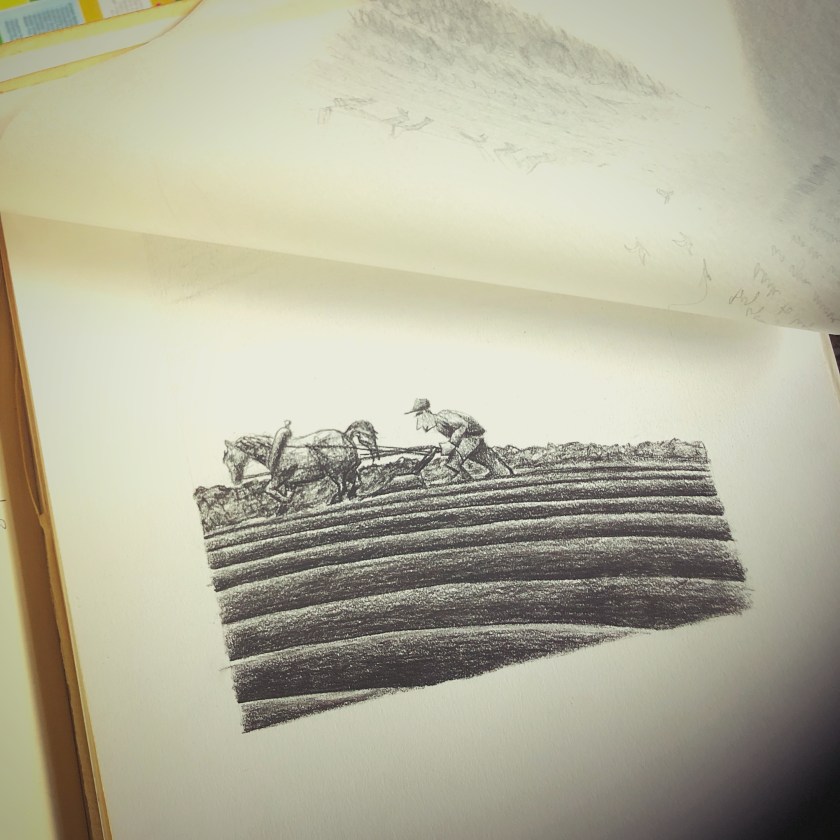

Before mobile devices with cameras — and software applications that capture images and store and share them — there was the sketchbook. A hard case, cloth-cover book featuring at least a hundred blank archival pages was always within reach. As a young art student it was my practice to draw advertisement layouts, images, typographic arrangements, or other sources of inspiration that I might use in future creative projects. Occasionally a sketch was a hand-drawn duplication of a photo, print ad, or poster. More often it was an interpretation, re-imagining, or riff on an original source of inspiration. It was, and is, how I learn — how I study. It is tactile.

The practice of drawing develops the interaction of muscle and neural growth. Drawing is a skill that will not improve by machine learning or multimodal image creation software applications. It is a dance between the muscles of the hands and fingers in coordination with the eyes and the cerebral cortex. Outsourcing these skills only lead to atrophy of intellect and muscle. Looking at my hands as they hover over the keyboard, I wonder why I am not drawing instead of typing. This too is a dance. The delicate steps navigating life’s dance among digital and analog tasks.