If “language is communal” with the primary obligation of telling the truth, than poetry — the highest form of literature — is essential for addressing the fragmentation of communities and people.

If “language is communal” with the primary obligation of telling the truth, than poetry — the highest form of literature — is essential for addressing the fragmentation of communities and people.

Thirteen years ago, my wife and I hosted friends at our cottage on the outskirts of Asheville. A simple meal of salad, chicken and pasta, and red wine provided the vehicle for conversation and stories.

The husband told a story about being pulled over by local police near Old Fort. The officer asked for the husband’s driver’s license and registration. The requested items were provided through a narrow slit of a rolled down window.

“I still have to roll the window down,” he smiled. This attested to his mountain frugality and blue collar virtue.

The officer returned the license and registration and asked if he knew why he had been pulled over and if he had firearms.

“No. And yes,” he replied. The officer asked where the firearms were located. He told the officer that the guns and ammo were stored separately in the trunk. He was then asked to get out of the vehicle and show the officer the guns. Which he did.

The trunk was opened to reveal a chainsaw, climbing equipment, tools and containers for guns and ammo. The officer admired the make and model of one pistol. Asked what he did for a living. And requested to handle the pistol. The husband complied. The officer inspected the pistol. To the husband’s surprise, the officer commented that he would tell his wife about this. She might buy it for him as a birthday gift.

“Well,” said the officer. “Have a safe drive home. And repair that busted tail light within the month.”

I admired the husband’s story. His stories were like climbing a mountain road that rose and fell and wove between cove and valley and eventually arrived were it intended.

That night, as the dishes were cleared from the dining table and a second glass of wine poured, his wife shared that she and her mother planned to attend my reading at Malaprop’s Bookstore and Café on Thursday night. She confessed that she was looking forward to the scheduled night of poetry and music. But she wanted to know why I chose to read and write poetry.

“Why not stories?” she asked.

That question haunted me.

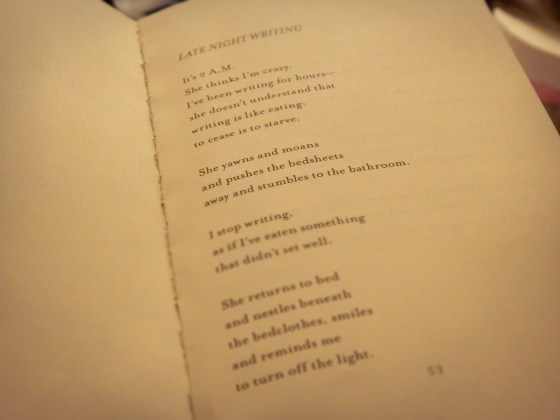

Poetry’s form and function is different from prose. It is more ancient. Where a novel’s exposition provides a landscape of hundreds of pages to expand the narrative plot of character, conflict, and theme, a poem compresses an idea, thought or theme into a few lyrical lines. This is an overly reductive and non-academic comparison of the two forms. But consider the etymology of the word “poetry.”

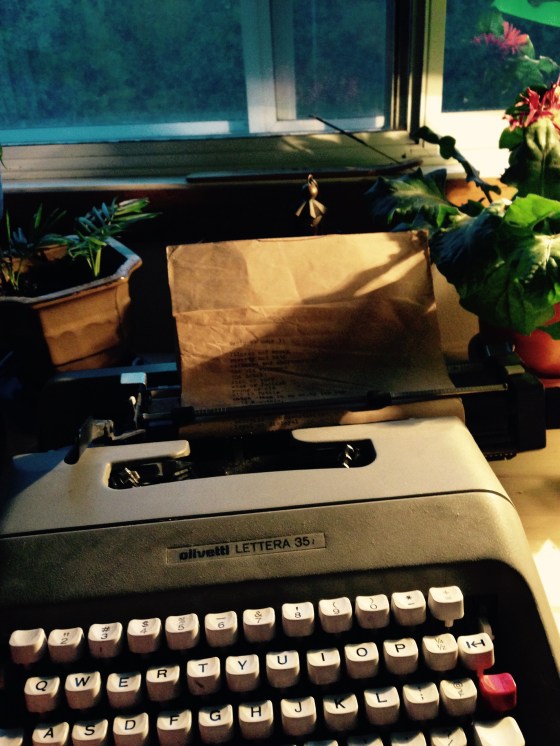

The English word for poetry comes from an ancient Greek word meaning “to make” or “to craft.” The German word for poetry comes from a Latin word meaning “to dictate.” The Romans often borrowed Greek ideas and themes and aped or improved them. Between the two etymologies I gather the impression that poets are conduits for The Muses — the source of inspiration and creativity. Poets dictate the message of The Muses. Poets craft the message of truth. The ancient Greeks invoked The Muses at the beginning of poems, hymns and epics.

At the time of the diner with friends, I held a casual understanding that poetry in the German language encompasses a compression or density of thought and theme. And that poetry in English embraces beauty and harmony–or graceful elegance. Then, as much as I could afford, I studied Persian, Chinese, Japanese and Korean poetry. And I learned there is much I did not know about continent of poetry.

“Why not stories?” she asked. Stories are important. Poetry is essential. Community is vital. Words must nurture a fractured community in order to bring it together and make it stronger. That August Asheville evening, more than a decade ago, was one of the last nights our two families enjoyed supper and stories together.

People leave. Find a better job. A greener pasture. Or at least a different job with a different view. Change is the only constant. The transience of American culture enables people to move every few years. Words, idioms and phrases fall in and out of fashion. How then are we to nurture a strong community? Maybe it requires each of us to dwell deeply and stand by language. Stand by words.

If “language is communal” with the primary obligation of telling the truth, than poetry — the highest form of literature — is essential for addressing the fragmentation of communities and people.

If “language is communal” with the primary obligation of telling the truth, than poetry — the highest form of literature — is essential for addressing the fragmentation of communities and people.