“Only idiots and the self-deluded think that being able to self-publish qualifies them to write,” concludes one person commenting on Two reasons why not to self-publish your book. It’s true. Not every self-published author writes well. For that matter, not every best-selling author writes well. I do agree in part with that comment–the logical part, not the jaded part. Like I said before, I am an advocate of self-publishing, but my views are changing.

Regarding self-publishing, I wrote a multi-part series titled The Economics of Writing. The basic premise of the series is this question: Why should a poet/writer spend his/her money on literary contests when they might self-publish his/her own work? You can read the whole series by following the links. What prompted the series was:

- I’ve been in publishing for a while and know how much it costs to produce and distribute print products and

- I read a story about a writer that spent more than $14,000 in a seven-year period on contest entry/reading fees, related postage, sample journals, literary memberships and writing conferences/workshops and won a $500 cash prize during that period.

I’ll avoid the analysis of literary contests [read about them in the second part of the series], and move to notable poets and writers who have self-published their work: Margaret Atwood, T.S. Eliot, Robert Service, Nikki Giovanni and Viggo Mortensen [read more details in the third part of the series].

When you consider the amount of time and energy–not to mention money–it takes to publish a book, self-publishing is an option to consider if you don’t want to wait for a publishing house to release your product. A poet and/or writer may spend years working with an agent to secure a book deal with a traditional publishing house. Whereas, self-publishing a book can make its way to the market in a matter of days or weeks.

Most self-published authors fail with their book releases in the following three areas:

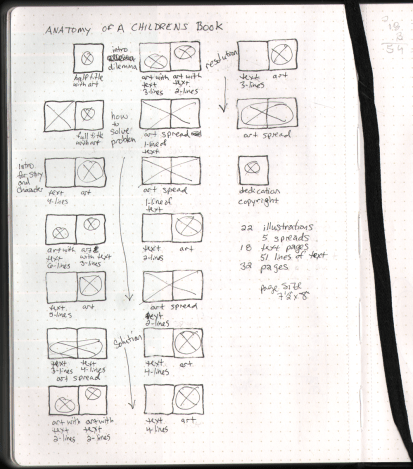

- Cover design. And in general, book design. Just because you cleverly wrote your major literary work in MS Word does not mean you can print it in MS Word. Let a professional graphic designer package your literary endeavor. Further, just because you have Adobe products loaded on your fancy schmancy MAC machine, doesn’t qualify you as a designer either. Book design is not the same as designing a web site (that you really borrowed from WordPress or some other blog platform and told your client you designed their web site *sigh*). A book cover is the movie poster for the book. It must invite, entice, and coax readers to pull the book from the retail shelf (or etail shelf), read the back blurbs and first chapter, and ultimately buy the book.

- Editing. First draft, best draft is not the best practice in selling books. Having your ever-loving mother to review your manuscript is not that same as getting your manuscript edited. Even a good writing group is not enough–but it is a very good start. Hire a good editor to work on your literary masterpiece. A good editor will make a huge difference in the final product. So much of self-published books are deficient in quality work. There are gruesome typos, grammatical crime scenes, and abominable stylistic failures. A good editor is like a good film producer–a poet/writer may have the vision, but the editor knows best how to articulate it to readers. A good editor is one of your best friends. The last thing you want to do is release a book product that you immediately have to print a second revised edition because you used “their” instead of “there.”

- Production efficiency and quality. The financial bar has been lowered in matters of producing a book. Print-on-demand options are more affordable now than ever before. But more affordable doesn’t always equate to quality book product. A lot of do-it-yourselfers enjoy the look of the Etsy-ish, handcrafted book products that clutters the indie poetry and zine scene. And that’s fine. Those products are souvenir. People who purchase those items understand that they are a souvenir, book art object. But that option is more expensive than one might suspect. Consider a book’s cover price of $12 per copy for a 64-page literary chapbook. Most traditional publishers have a production markup of no less that 12 times. If, for example, the cover price is $12, than the book’s production cost–printing cost, cover art, book design, etc.–on a 1000 copies print run is $1 per copy. Most self-publishers don’t consider this fact and usually spend $6 per copy on a print run at Kinkos for a run of 100 copies. At that rate, it’s a hobby not a business.

I’ve been on both sides of the argument. I’ve self-published books that failed and succeeded. I launched two book imprints within a media organization that sold over 30,000 books in a couple of years. And here’s where I’m changing my position on self-publishing versus traditional publishing: idealism versus reality. Poet and blogger extraordinaire, Ron Silliman, offers these thoughts on idealism versus reality when he suggests that it would be ideal:

…if all bookstores carried every book of poetry that is in print… and if all poets had equal access to book publication.… But until then, it’s the real world I’m going to engage with…

So, where does that leave authors who don’t have a literary agent and don’t want to wait years and years to get their work published? Co-publishing. There are several reputable publishing houses that offer co-publishing services. A poet/writer still pays for the production of the book product, but the publishing house offers editors, publishers with decades of experience, a professional art department, a public relation staff, a warehouse facility, events coordination, distribution and other services. Consider the question that sparked the multi-part series I wrote. As a writer, would you rather spend seven years and $14,000 trying to win a literary contest and/or land a book deal? Or spend $14,000 and seven years selling your book, earning new readers and working on your upcoming books?

How do you capture an abstract thought for a book cover design? That’s the question one person left in the comments section to

How do you capture an abstract thought for a book cover design? That’s the question one person left in the comments section to