Breakfast with brush and paper

Before mobile devices with cameras — and software applications that capture images and store and share them — there was the sketchbook. A hard case, cloth-cover book featuring at least a hundred blank archival pages was always within reach. As a young art student it was my practice to draw advertisement layouts, images, typographic arrangements, or other sources of inspiration that I might use in future creative projects. Occasionally a sketch was a hand-drawn duplication of a photo, print ad, or poster. More often it was an interpretation, re-imagining, or riff on an original source of inspiration. It was, and is, how I learn — how I study. It is tactile.

The practice of drawing develops the interaction of muscle and neural growth. Drawing is a skill that will not improve by machine learning or multimodal image creation software applications. It is a dance between the muscles of the hands and fingers in coordination with the eyes and the cerebral cortex. Outsourcing these skills only lead to atrophy of intellect and muscle. Looking at my hands as they hover over the keyboard, I wonder why I am not drawing instead of typing. This too is a dance. The delicate steps navigating life’s dance among digital and analog tasks.

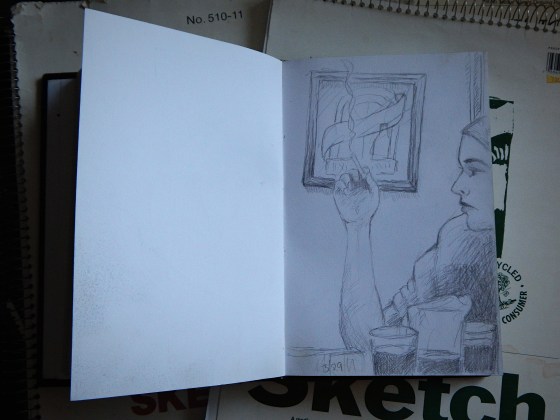

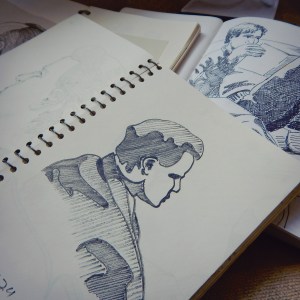

Previously mentioned, the above image is an old sketch of the Luther Terry painting.

On weekends, I visited an art museum when I was younger. With pen and black cloth sketchbook, I recorded the painting in to my sketchbook. Practiced drawing. Researched an allegory.

But capitalism is a poor cultivator of the arts. For the price of an item of beauty and value, some would pay the same price for a 728 pixel wide by 60 pixel high web banner. A digital item that pastes at the top of a web page or email for a week or two and then disappears.

The lesson I quickly learned is that beauty is not useful. Art and design that is practical and commercial are valued in America. Sacrifice the permanent on the alter of immediate. This utilitarian principle fuels professional success. Or at least provides employment.

This drawing in my sketchbook reminds me that I once believed that beauty is lasting. And, I still do.

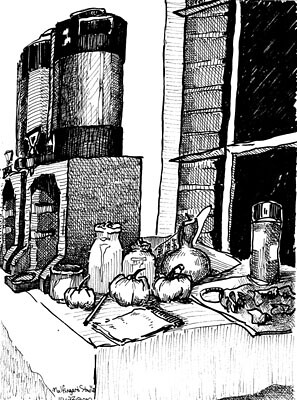

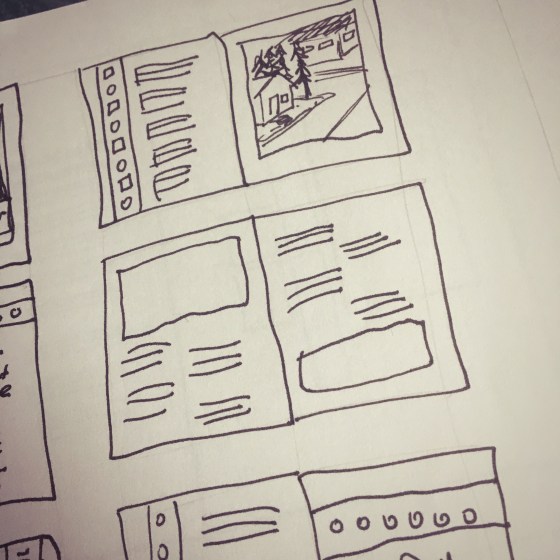

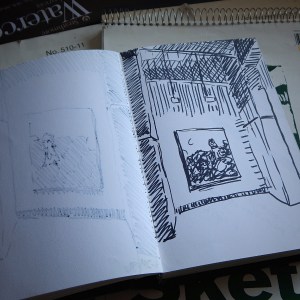

What do you do when you find a 15-year old sketchbook with at least two dozen blank pages at the end of it? This sketchbook was something used many years ago to compose page layouts ideas.

It may be that as a young graphic designer I required the use of pen, ink, and paper to organize thoughts and ideas before turning to the digital tool of computer and software to complete a magazine page layout. Or a book layout. Or whatever design project it was that I was working on at the time.

Even back then, a lot of creatives were skipping the hand-drawn phase of graphic design and moving to digital sketches. I was one of those designers too. It did not take long to adapt to digital sketches using Quark Xpress or PageMaker. External and internal clients did not understand these hand-drawn sketches. I quickly understood that these initial sketches were best served between fellow creatives. A form of pictorial shorthand.

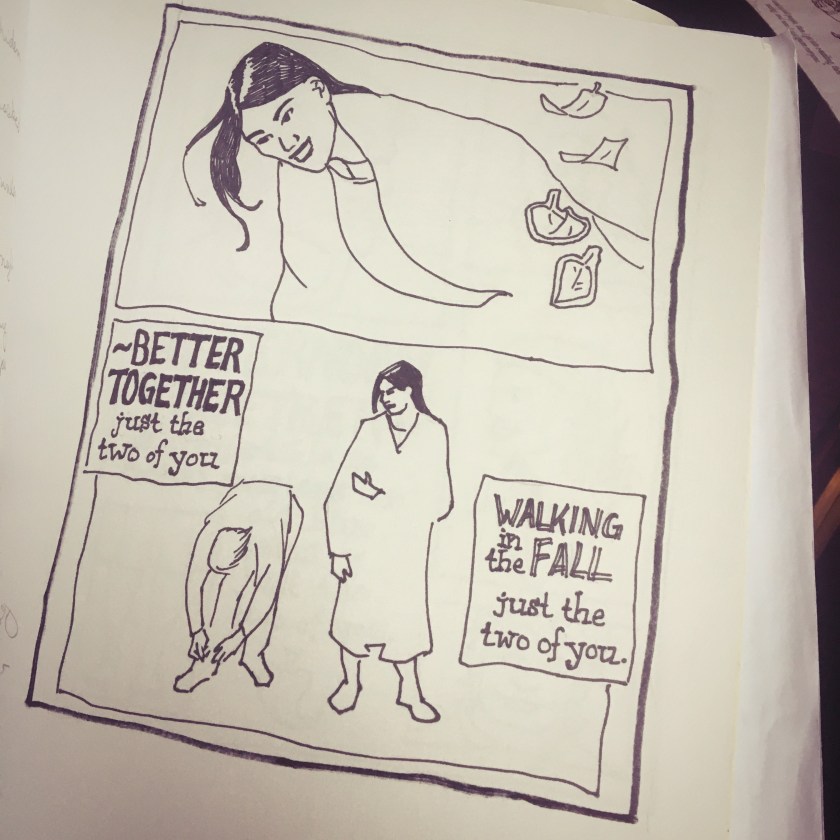

Sketches using human figures engaged clients. A point of connection. Composing advertisements and editorial layouts was enjoyable. Even when it was poorly drawn it was pleasurable. It was exciting to explore and play out ideas on pages. To balance text and image. To push the elements toward asymmetrical tension.

Sometimes referred to as “mock ups” or “work ups,” these comps (jargon for compositions) often featured ad copy or editorial headlines that I wrote. I preferred writing my own copy rather than using dummy copy, greeking, or some other form of gibberish used to represent where text was to be placed in design compositions.

These sketches bring back a lot of memories. Projects completed. Projects that never were approved. Abandoned. Like the craft of sketching designs and ideas.

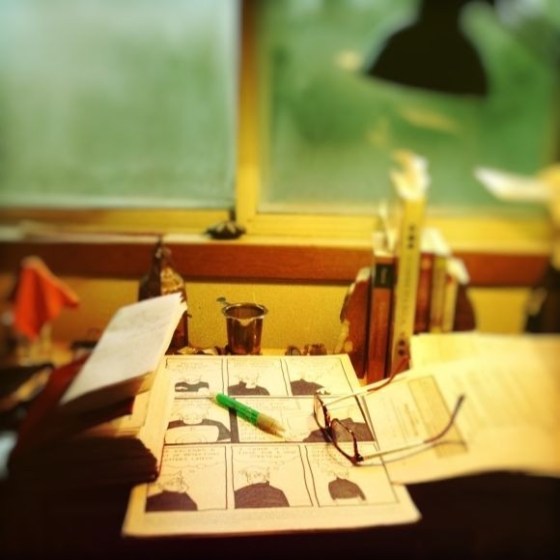

I needed something to prop up the office laptop computer in order to avoid a kink in my neck as I work on print and web design tasks. MacBook Pros are not ergonomically designed. An old keyboard was located. And then a Kensington trackball mouse. And an old, unbound sketchbook. That did the trick.

This work-from-home solution is not ideal. There are days when my children see that I spend most of the time reading and replying to emails, joining video conferences, and moving file icons across the desktop to various folders synched to cloud-based servers. Graphic design looks so different from the point at which I joined the trade. It is less tactile.

The national safe-at-home quarantine allowed me to build a wood desktop and a wood stand-up-desk solution for the laptop, keyboard, trackball workplace arrangement. And the 15-year old sketchbook? Well, paging through the collection of ideas and designs. . . after a long hiatus, I began sketching and drawing on the empty pages at the end of the book.

Relocating to Wisconsin was done with such haste that I am still discovering unopened boxes of items. Some items I have not seen in years. One such discovery was a series of old sketchbooks.

A five-minute sketch of a landscape painting on display at an art museum. The composition captured, but not the details.

A loose sketch of a production of Shakespeare in the Park.

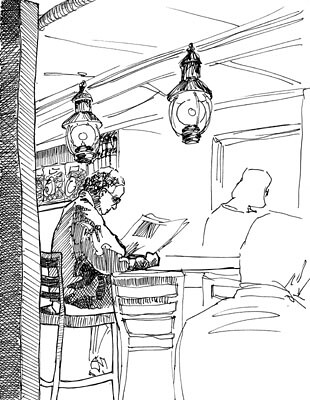

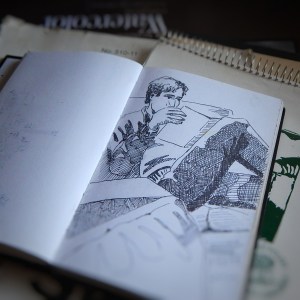

A 30-minute sketch of a roommate reading a magazine. That was back in the days before mobile phones, tablets and laptop computers.

When I flipped through the pages of these sketchbooks there was a mixture of despair and some other unnamed emotion. Is it possible to name every emotion? Is it necessary to catalog everything in the cosmos in hopes of gaining understanding? Or knowledge? Or wisdom? But I digress.

Each sketch had a story. The night at a downtown pub when I learned I was no good at billiards. After the first game, I enjoyed the rest of the evening by doing sketches. I remember the show at the art museum and the artist represented. The friends who invited me to see Shakespeare in the Park. And the rare moment a very charismatic roommate sat on the couch before jetting off to a concert or movie or date or some other activity.

A sketch is an exercise that precedes a painting. But these sketches never received the intended painting. Reportedly, Thomas More’s poems for Epigrammata began as a Latin translation exercise. If I view these sketches as lost paintings, I despair. But if I view these sketches as exercises, I am gratified.

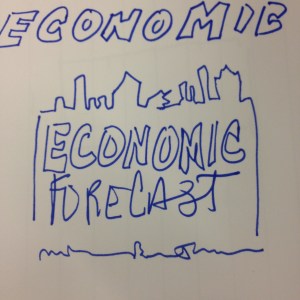

The practice of sketching is an exercise and preliminary draft of an art object. Even today, I still sketch ideas and images. For example, I was asked to create a logo design for a business event.

After some discussion the request included the city skyline of Milwaukee.

Once a plan was in place, I quickly moved to a digital rendering of the logo design and colors. Securing a piece of stock illustration, I customized the vector image and crafted a logotype used to promote and represent the business event.

The pace of work is so fast, months go by without me realizing the value of the brand created. What took hours over the span of a few days, was on display on the front page of the newspaper and behind a representative from the Federal Reserve Bank in Chicago.

A few small three-inch square pen sketches became a huge display banner at a business event in Milwaukee. The practice of sketching is twofold: exercise and exhibit. The path to the 2019 Economic Forecast event logo and banner was a thousand unseen sketches. Page after page. Year after year. A lot of practice pieces that remain lost from view. But without them the objects that are visible would not have been created.

What does one do with old, unpublished artwork? Dozens upon dozens of illustrations remain hidden. Housed in art portfolio cases and cardboard boxes. These sketches, drawings and illustrations remain artifacts of decades of work.

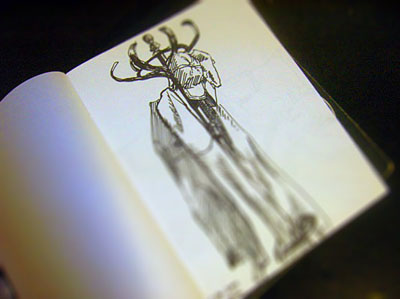

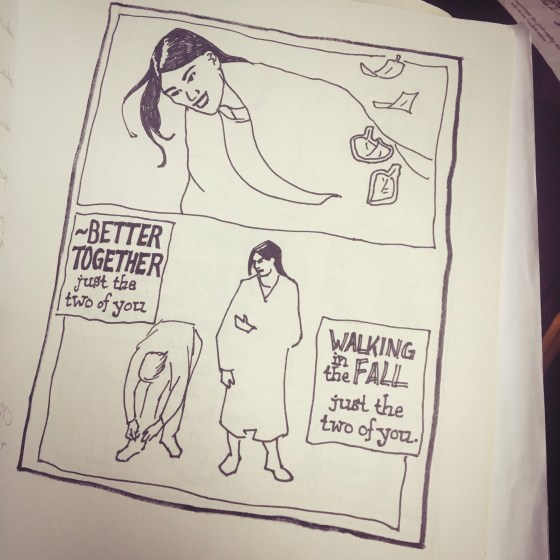

They resurfaced this summer. Drawings and illustrations created with the purpose of advancing a career as a children’s book writer/illustrator, comic book artist and/or cartoonist. Several four-page comic book stories present an exercise toward a full-length comic book. Inspired by the 1990s indie comic scene, a lot of the stories are slice-of-life scenes and dramas. One collection of illustrations is a story written by a friend. Another set of drawings features character drawings for a writer seeking to pitch a proposal to Image Comics.

There is a portfolio case filled with pages of a first issue and half a second issue of an indie comic. It was created for a writer who contacted me to collaborate on the project. The pages display pen and brush illustrations. Think of the early work of David Collier. If he drew every page with his right hand. (He is left-handed. If I recall correctly.) On second thought, maybe it doesn’t look anything like David Collier’s work. The struggle with this indie project was that I learned that I do not illustrate fast and well at the same time. Back in those pre-iPhone/pre-Twitter days, I worked as a graphic designer during the day and an artist by night. A 30-day deadline to complete 22 pages plus cover art was a difficult task. If I had worked eight hours a day on the project instead of two hours a day, maybe the results would have been better. The indie comic was never published.

Another sketch book has pages of comps for a cartoon strip. The idea was that if I cannot draw detailed panels and pages fast, maybe I can draw cartoons faster. So, I created a cartoon character and comic strip and discovered that drawing a cartoon is just as time intensive as illustrating detailed comic pages. I pivoted toward a cartoon style similar to Jim Davis. In short, a comic strip with near static panels and subtle changes in art between one panel and the next. Sort of a pre-Adam Ellis templated four-panel strip. The comic strip was published regularly in a North Carolina alternative newspaper until the paper took an extended sabbatical.

“I like that one,” my bride commented. Dozens of cartoon pages rest on a desk in our bedroom.

“Maybe I should collect these pages into a book,” I offered.

“What do mean?”

“You know, like an artist’s sketchbook or portfolio book. I’ve got several of those type of books.” I think of books like Michael Wm. Kaluta Sketchbook or C. Vess Sketchbook.

“Yeah, but aren’t those more like retrospectives of an artist’s celebrated career?”

“Hm. Yeah. I guess you’re right,” I answered. But why can’t it be used to promote a career, I think to myself.

“Maybe after you’ve published your magnum opus.”

“Yeah. I guess so.”

The illustration boards still rest on the desk I built from salvaged wood. A reminder to keep going.

Personal archeology.

Discovered these old sketch books in September. Looked at them. Placed them on a shelf. Lost them again.

Rediscovered the sketch books again this weekend. Marveled at how much time was invested. Considered how these books were populated with sketches of classmates, drawings of roommates and other ephemera in a place and time were smart phones, tablets and laptops were not ubiquitous.

Question:

What would you be able to create if you were not glued to your smart phone for more than four hours[1] a day?

NOTES:

The final page of a sketchbook is a peculiar geography. . . read more ->

Somedays a walk to the river is a remedy. Amid . . . read more ->

Years ago, the practice of capturing a moment or event was accomplished with pencil and sketchbook.

For years have pushed art making away from me. Partly due to lack of space and consolidating my paintings into small sketchbooks. Then I replaced paint for pen and ink, and drew smaller images into Moleskines until my drawings disappeared into lines of characters trying to form poems…

Now, I want to start painting again…

(Image source via creativeinspiration: 472239364: artpixie: love letters and skypaints: http://www.flickr.com/photos/tinycastles/3912498882/)