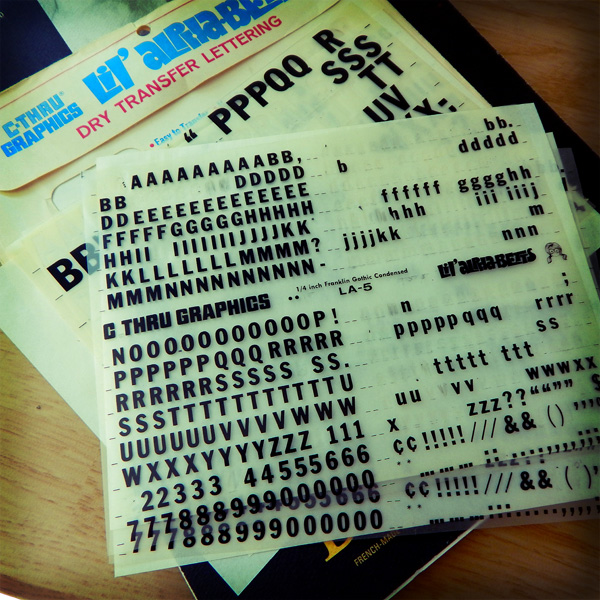

From the graphic design archive…

Anyone remember doing advertising or editorial mockups using dry transfer lettering? Or the fact that mockups were expected to take days not hours?

From the graphic design archive…

Anyone remember doing advertising or editorial mockups using dry transfer lettering? Or the fact that mockups were expected to take days not hours?

When I looked at my office desk earlier this week, this question came to mind: Does this make me look Luddite? On the desk was a book on the subject of graphic design, a daily desk diary, a periodical, a mechanical pencil (not pictured), a tin of tea and cup of tea (also not pictured) and a smartphone (not pictured, because it was used to capture the image).

It does not escape my attention that I could use an internet search engine to locate similar content that I found the printed book. But I chose the book. And there are plenty of cloud based software applications that I could use to plan and track daily activity. But that was not my choice. A mechanical pencil is easily replaced with a keyboard and mouse. Again, that was not my choice. To my knowledge, tea cannot be digitized. At least not yet. And the smartphone. Well that is a device that continues to intrigue and perplex me. It is advertised to make life easier, smarter. But I have yet to get it to produce a good cup of Earl Grey tea on a misty morning when I’m tearing down the mountain to get to the publishing house to invest in another book project.

Wear the blue neck tie to suggest boldness and confidence. Wear the red tie for passion. Or so the conventional wisdom offers those business persons who are presenting themselves for a job interview. Color is important when designing books, posters, web sites, etc. Building an effective color palette takes years of experience in knowing the right color combinations that present contrast or harmony or various other arrangements.

Thanks to some online resources, creating a color palette takes only a few minutes. Here are four online tools to use in creating a customized color palette.

There is also a way to create a color matrix using Adobe Illustrator, but that’s a bit more involved and takes longer to explain. Here’s an example of what a color matrix looks like (see below).

What tools do you use to create effective color palettes?

It is still a bit odd for me when I see the title of “Creative Director” on the labels of mail and packages that are delivered to my office desk. I won’t deny that so many years ago, sitting in graphic design class at the university, I dreamed of being a creative director. But now I look at that designation, that job title, and wonder.

What does a creative director creative director do anyway? It is too reductionistic to say that a creative director is the primary enforcer of consistant brand and mission of a company. The job is more nuanced. One professional states that the “job doesn’t come with operating instructions.”1 [1] That is absolutely true, at least, in my case. There’s more I could write about the path to a creative director or even the role of a creative director, but that may be for a different post.

What makes me wonder about the designation of job title of creative director is what it means. Is it my identity? Yes. No. Does it matter? It seems that the title is more of a way for other people to catalog and/or judge me, but it is not who I am as a person. Does that make sense?

NOTES:

1) Mary McMahon, “What is a Creative Director?,” Practical Adult Insights, Accessed January 15, 2013, https://www.practicaladultinsights.com/what-is-a-creative-director.htm

(image via Jonathan Trier Brikner)

There’s more to being a design genius than this. Truly.

Just because you have a computer, laptop or tablet allowing you to download free fonts and free images and use some free app you discovered on Twitter does not make you a design genius.

Just because you “designed” a cool graphic image the way many misled souls believe they labored and “built” an IKEA bookshelf does not make you a design genius. [1]

Celebrated graphic designer, Milton Glaser, put it best:

Computers are to design as microwaves are to cooking.

Good design solves problems and presents stories. As a creative director for an international publishing house, my chief goal is to attract potential readers to new books by capturing a story in a single cover image. To illustrate the point further, an author (for whom I had just completed a book design) emailed me recently: “I’m getting some great feedback on my Facebook page about the cover. Thank you very much…” Good design is about communication: problem solved, story told.

NOTE: [1] For what it is worth, IKEA is not good design. It is nothing more than cheaper-than-Wal-mart veneer furniture, second-rate fabric products and wax-paper lamps. And don’t call IKEA “modern design” because modern design is so 1948. Seriously, the modernist movement began almost a century ago. But I digress.

Something hides in the closet. Below the button down shirts and dress slacks for work, behind the winter wardrobe of sweaters, vests and jackets, and against the back wall is an old black leather portfolio with handles. Years ago it was a mandatory item for any and every graphic design student or young professional with goals of becoming an art director, illustrator or creative director. I pulled out the old portfolio and the oversized heavyweight document envelopes behind it and entered a gateway to another time and place.

Like time travel, I am back in the 1990s. There were three main portfolios I presented. One presentation was corporate, ad agency design samples. The kind of material that ranged from logo design, brand campaigns and the like. The second presentation was print design. That portfolio exhibited all manners of print designs from brochures, books, direct marketing collateral, magazine spreads, cover designs, etc. For presentations, I would rotate the design samples in the black leather portfolio based on the interview. Sometimes I presented a hybrid of both that included work that featured my copyrighting and marketing pieces. But the third portfolio was my favorite–the illustration portfolio.

Professors, peers and even my first art director advised it was the weakest of the three. The general critique was that technique needed improvement. So I kept working on improving technique and execution. A black cloth case bound sketch book always accompanied me almost everywhere I traveled. I’d sketch landscapes, still lifes, portraits and tried various techniques using pencils, Sharpie markers, charcoal, ink and watercolor. But soon I learned that I could earn more financially and find more consistent work with digital designs.

It is not that I abandoned illustration. A few years ago, a national news magazine featured one of my illustrations on the cover of its annual books issue. Earlier this year, another illustration was featured as a book cover design. Also this year, a few spot illustrations were published in a book.

As I look at these old illustrations and sketches, I see a younger, self-doubting me at a time before home computer, internet, or smartphone entered my life. Back in those days, the only entertainment devices I had was a stereo set with a five-CD player, a stack of maybe 30 audio CDs and a shelf full of books. Through the portal of this time capsule, I see the mistakes and accomplishments with a new perspective. Hidden away in that closet is a portfolio of dreams, aspirations and ideas that was slowly replaced with a portfolio of duty and responsibility. A thought occurs to me as I examine an unfinished sketch of a female portrait, did I focus on pursuing a career path rather than a vocation? Maybe that is a thought I should hide in the closet while I bring some of these illustrations into the daylight.

Sometimes a few notes of music follow you for days are weeks or years. Sometimes a line of poetry haunts you like a memory you can’t quite recall. It’s like rain, it permeates the air, wets the ground, even makes tea taste more pronounced.

Here’s part of a story I can share with you. After I was at university studying art and design, I found an audio CD in a music store titled Jazz for a Rainy Afternoon. What attracted me to the album, a compilation, was the fact that the cover art reminded me of a sexier version of Gustave Caillebotte’s famous painting. I purchased the audio CD. It was background music initially. Something to edge off lonely days as a poor graduate beginning a career in graphic design. About the same time I discovered, and purchased, a copy of William Kistler’s poetry book America February.

I have always enjoyed poetry and music, but reading Kistler’s work was rigorous for me. Light verse and traditional poems, the variety that fill American and English school book anthologies, were what I was familiar with. But Kistler’s poetry was a new dish for my inexperienced palate. Equally, understanding the musical selections of Jazz for a Rainy Afternoon as more than a background soundtrack was challenging.

A line from one of Susan L Daniels’s poems has captured my attention this past week—the way jazz and poetry sometimes do. The speaker in the poem answers a question, so you like jazz, by saying: “…the answer is no/I live it sometimes…” That’s what I have come to enjoy about the complicated progression in a song or a poem that avoids a clean resolution.

Jazz and poetry work into you. It takes you down that familiar path of a rainy day afternoon, a common enough subject, but it is a variation of that theme. Never the same way twice. Like reading a poem as a school boy and reading it later as a graduate and later as a professional. Same poem printed on the page, but different. Always different. But familiar, because you “live it.” There’s more to this story. Maybe I’ll share it with you on another rainy day afternoon.

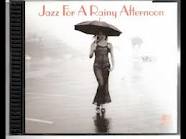

For me, every book cover I design begins with pencil sketches that eventually lead to ink drawings. Actually, I suppose it begins prior to that. The author receives a pre-publication questionnaire from me prior to the design process. The questionnaire asks the author what is his/her elevator pitch, what are the pillars of the book (i.e. what are three main concepts/ideas in the book?), and what is the book’s key audience? There are more questions that help me prepare for the design process, but reading through that document helps me form an idea of who the author is, what the book is about and how best to represent the book’s content with an attractive cover.

For me, every book cover I design begins with pencil sketches that eventually lead to ink drawings. Actually, I suppose it begins prior to that. The author receives a pre-publication questionnaire from me prior to the design process. The questionnaire asks the author what is his/her elevator pitch, what are the pillars of the book (i.e. what are three main concepts/ideas in the book?), and what is the book’s key audience? There are more questions that help me prepare for the design process, but reading through that document helps me form an idea of who the author is, what the book is about and how best to represent the book’s content with an attractive cover.

Then I receive the manuscript a few weeks later and begin reading the author’s work. This helps try to envision in my mind an iconic poster image. For me, a book cover is the equivalence of a film poster. At this stage, I produce some concept drawings (like the one’s pictured) and research color schemes and subject themes that I plan to use in the cover design. After a couple rounds of emails with the author, I proceed to the full-color design phase.

The full-color design is often photographic, as in the case of this sample, but can also feature illustrated work or typographic designs. An illustrated cover is sent to a freelance artist who spends a week or so producing the cover art. The final cover design pulls together all the elements (art, photo, type and copy) to present a cover that, in theory, sells a 1000 to 3000 copies on face value. I know what you’re thinking, but books really are judged by their covers. Just watch people at a bookstore. They’re scanning covers before they even pick up a book to read the back copy blurb or open a book to read the first few chapters. If a book has amateurish art or less than professional photography, the audience will move to the next book cover that has great photography or stunning artwork. Further, if a book has poor quality cover art, it will be represented in poor book sales. Let me say it again: if a book has crappy cover art, the book will have crappy sales. No reader wants a crappy book on their bookshelf or e-reader. Half the battle for a reader’s attention is getting him/her to pick the book from the shelf. The same applies to e-book stores. Readers are scanning covers from the Kindle or Nook e-stores and deciding, based on cover design and book blurb, what title to purchase.

The full-color design is often photographic, as in the case of this sample, but can also feature illustrated work or typographic designs. An illustrated cover is sent to a freelance artist who spends a week or so producing the cover art. The final cover design pulls together all the elements (art, photo, type and copy) to present a cover that, in theory, sells a 1000 to 3000 copies on face value. I know what you’re thinking, but books really are judged by their covers. Just watch people at a bookstore. They’re scanning covers before they even pick up a book to read the back copy blurb or open a book to read the first few chapters. If a book has amateurish art or less than professional photography, the audience will move to the next book cover that has great photography or stunning artwork. Further, if a book has poor quality cover art, it will be represented in poor book sales. Let me say it again: if a book has crappy cover art, the book will have crappy sales. No reader wants a crappy book on their bookshelf or e-reader. Half the battle for a reader’s attention is getting him/her to pick the book from the shelf. The same applies to e-book stores. Readers are scanning covers from the Kindle or Nook e-stores and deciding, based on cover design and book blurb, what title to purchase.

From the time the final cover is approved until the product arrives is six to eight weeks depending on circumstances. That’s when the real test of a book’s cover design and interior content begin. And that’s about the time I begin the next round of cover designs.

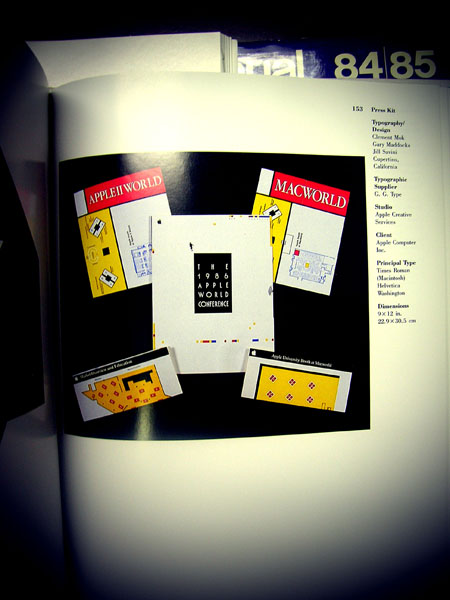

I loved reading these kind of articles in Step-by-Step Graphics magazine.

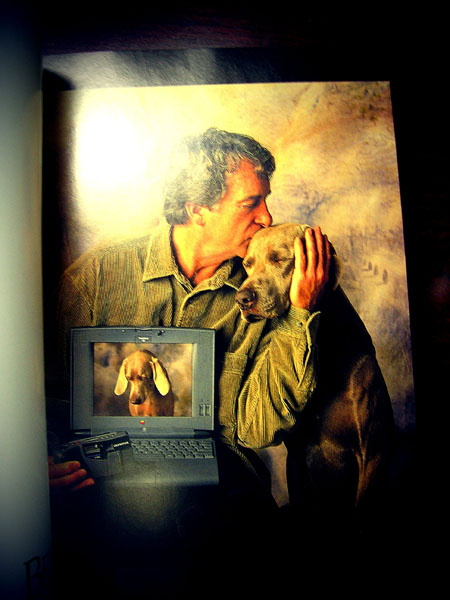

Check out this old Apple Computer ad for the late 1990s. #design #apple #mac

Better yet, does anyone have a Zip drive?

Does anyone still use these old Pantone color guides?

Cleaning out an old desk and discovered these books.

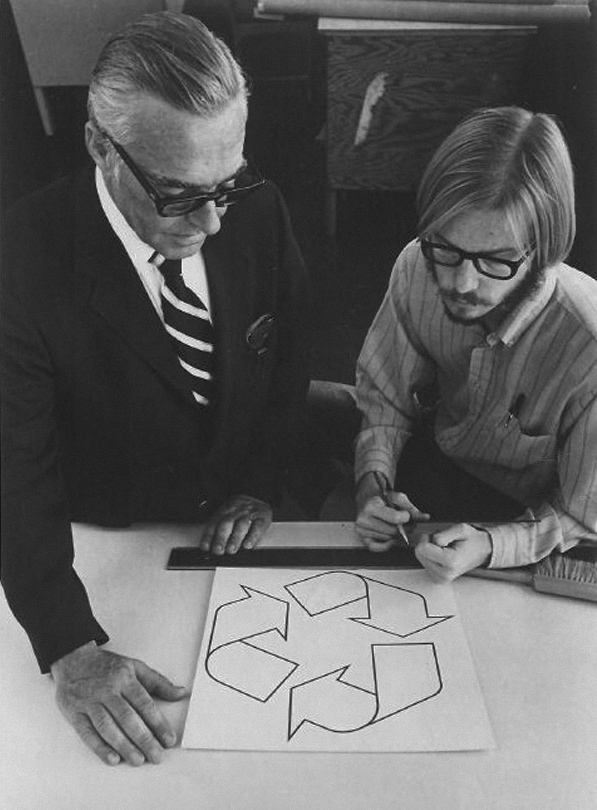

Gary Anderson (right), creator of the recycling symbol, 1970.

Anderson was a 23-year-old USC Architecture graduate when he entered the Container Corporation of America’s design contest to create what would become the universal symbol for recycling.

(via waxandmilk) 1

( via noonebelongsheremorethanyou) 2

(via brocatus) 3

NOTE:

1) Mark Malazarte, waxinandmilkin, accessed September 17, 2010, https://waxinandmilkin.com/post/963308730/gary-anderson-right-creator-of-the-recycling Tumblr account deactivated.

2) noonebelongsheremorethanyou, September 17, 2010, https://noonebelongsheremorethanyou.tumblr.com/post/964604837/anneyhall-gary-anderson-right-creator-of-the Tumblr account deactivated.

3) André Brocatus, André Brocatus was here…, September 17, 2010, https://brocatus.tumblr.com/post/964633674/noonebelongsheremorethanyou-gary-anderson

Earlier this week we did a post on a printed piece created by British design firm Spin that details the top 10 books from 50 major figures in graphic design.We sorted through the 500 listed books and found that there were 14 books that appeared in almost every list.

Here’s the list in no particular order:

01. A Designer’s Art Paul Rand

02. Typographie Emil Ruder

03. Mode en Module Wim Crouwel

04. A History of Graphic Design Phillip Meggs

05. Jan Tschichold: Typographer Ruari McLean

06. Design as Art Bruno Mari

07. 8vo: On the Outside Mark Holt

08. Tibor Kalman: Perverse Optimist Peter Hall

09. Weingart: My Way to Typography Wolfgang Weingart

10. Designed Peter Saville

11. How to be a graphic designer with…Adrian Shaughnessy

12. The Tipping Point Malcolm Gladwell

13. Modern Typography: An Essay in Critical… Robin Kinross

14. Envisioning Information Edward Tufte

NOTES:

1) Liz, “Follow up: Spin asks: What are the top ten books you believe designers should read?” accessed January 27, 2010, https://liz.tumblr.com/post/352754770/follow-up-spin-asks-what-are-the-top-ten-books

2) Plaid-Creative, accessed January 27, 2010, http://blog.plaid-creative.com/post/346685665/follow-up-spin-asks-what-are-the-top-ten-books-you (page no longer available, Tumblr account deactivated)

i went to school for graphic design, and did not spend my nights getting drunk. instead, i worked my ass off, spent most of my outside-class time learning/trying/doing as much as possible, and then got an awesome job after graduating.

protip: if you’re lucky enough (and i mean it when i say lucky) to be in college, you should be spending all available time learning, trying, making things, messing things up, experimenting and READING. (seriously. they make sketchbooks with words in them already. they are just called books.)

i didn’t waste a single day. and neither should you. build your momentum and go with it.

for the but-i’m-an-artist’s: you want money? learn a technical skill related to your field and get good at it. then get better at it. jonathan harris built wefeelfine on the weekends while working a full time job. just sayin’.

final note: i had a BLAST in college, and miss it like crazy. working hard does not mean no-fun-allowed, it means relax harder 🙂

orginal image via synecdoche

via DesignApplause

Good design is innovative

Good design makes a product useful

Good design is aesthetic

Good design helps us to understand a product

Good design is unobtrusive

Good design is honest

Good design is durable

Good design is consequent to the last detail

Good design is concerned with the environment

Good design is as little design as possibleDieter Rams (born May 20, 1932 in Wiesbaden) is a German industrial designer closely associated with the consumer products company Braun and the Functionalist school of industrial design.

In 1993 I asked Dieter to speak to the Architecture & Design Society at the Art Institute of Chicago. The society recently had a name change: “design” had been added. We joked ( ahem ) at the time that the real estate economy was so bad that the Architecture Society needed new members. We needed a credible and passionate design icon to speak to this group. Dieter became the first designer to speak under the society’s new name.

What I remember that night and again recently while watching the Objectified movie was Dieter’s 10 design principles. Honestly, I can’t tell you for sure that these are the same principles. Hoping Dieter will set the story straight.

I think I like the earlier stuff better. Maybe it was the materials or maybe it was so different than the pack at the time. The first Braun product I remember making a design connect to me was an electric razor. Much of Dieter’s work has long seemed more connected to brutalism than minimalism. Let’s say beautifully, brutally, minimal.

When describing what you want in a design, make sure to use terms that don’t really mean anything. Terms like “jazz it up a bit” or “can you make it more webbish?”. “I would like the design to be beautiful” or “I prefer nice graphics, graphics that, you know, when you look at them you go: Those are nice graphics.” are other options. Don’t feel bad about it,you’ve got the right. In fact, it’s your duty because we all know thaton fullmoons, graphic designers shapeshift into werewolves.

Ways to drive a Graphic Designer mad. #5. (via yyoyoma)

My new favourite is ‘I’d like it look more designed”.

(via misssnowwhite)1

NOTE:

1) Account deactivated December 2013.

Gary Sullivan on poetry book cover designs:

“Stephen Paul Miller’s Skinny Eighth Avenue… has enough design problems to send me quickly in the other direction…. screams not just DESKTOP PUBLISHING but PRINT ON DEMAND.

“In the 60s and 70s, amateurish often meant a simple type on a white cover with a hand-drawn black & white image. These items often have a kind of funky charm, and sometimes even elegance, to them…. With the rise of desktop publishing in the 80s, things began heading south. Link

Avoid scaring off potential readers with “desktop publishing/print on demand” covers and hire me a professional graphic designer.